The 2022 attack on the Nord Stream pipelines brought much needed attention to the vulnerability of maritime infrastructures and their vitality in the digital age and for achieving the goals of the green energy transition. The October 2023 Baltic Connector pipeline incident has given this agenda further impetus. Identifying a common agenda for policy and research to enhance Critical Maritime Infrastructure Protection (CMIP) in a dialogue between academia, industry and policy was the key objective of a symposium held in Copenhagen, 23.-24.11.2023.

Several key policy recommendations are by now common knowledge. These include the need to strengthen policy integration, operational coordination, multi-stakeholder dialogues, information sharing, monitoring and surveillance, including in the underwater domain. The goal of the symposium was to go beyond these recommendations, to broaden the perspective, and to develop a common understanding of activities and gaps within the North Sea.

The importance of regional seas and horizon scanning

CMIP should be addressed on the level of regional seas. The geophysical conditions, the legacy and planned infrastructures, threats and risks, legal arrangements and institutions and the political contexts fundamentally differ across regional seas.

The intensification of infrastructural development in the North Sea requires choices to be made about the best routes to security, particularly between resilience through duplication and redundancy, or protection, monitoring, and even deterrence for larger, more singular infrastructures. Currently, design choices are business driven, but given their importance, more strategic input and consultation are needed. The North Sea is an important security space, but also a laboratory for testing solutions and developing best practices for other regional seas.

CMIP requires a solid mapping of existing and planned infrastructures and how they are coupled. This implies anticipating infrastructure projects in the near future (e.g., wind farms), but also further ahead (carbon storage). Integrated modelling is needed.

Since infrastructures are planned to be operational for 20-30 years, CMIP is best based on long term horizon scanning of threat and risks.

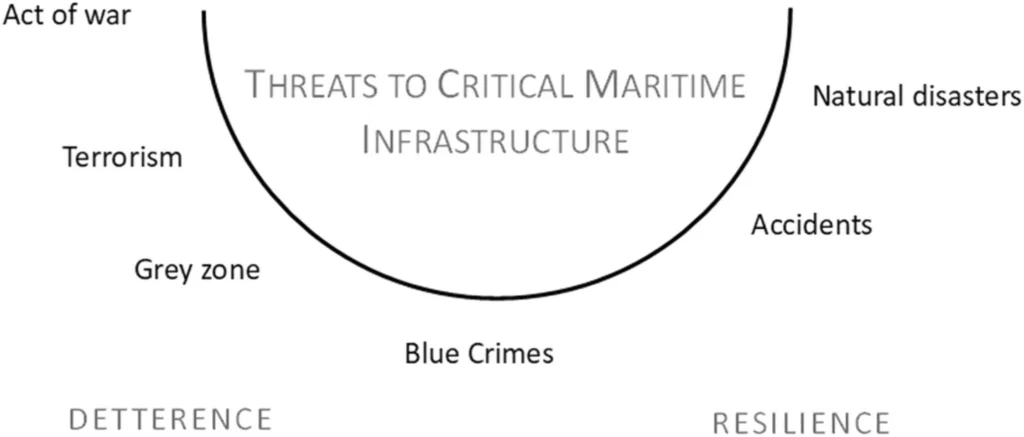

Landscape of threats and risks

Source: Bueger, Christian & Tobias Liebetrau. 2023. Critical Maritime Infrastructure Protection: What’s the trouble?

The question of which infrastructures are ‘critical’ and need closer protection continues to be weakly defined. Criticality can be established on the basis of two forms of analysis focused on 1) damage and impact, or 2) opportunity. Analyses of impact identify which material, economic, or symbolic damage could be caused by infrastructure failure. Opportunity refers to the easiness of attacking infrastructures without detection.

Maritime infrastructures differ from terrestrial ones, because of their opportunity structures. Access is easier, since no state boundaries are crossed, there is ambiguous maritime activity and less surveillance.

Which actors have what responsibilities?

The maritime infrastructure industry operates extensive self-protective means. These include protective designs such as covers to guard against anchors or trawls, remote monitoring by UAV, UUV or fixed sensors, and insurance policies where possible, self-insurance where not. More work is needed on the risk implications of installing security technologies on infrastructures and sharing their data with military authorities, such as whether this makes them a target and/or less insurable.

Key questions continue to be: Which self-protective requirements should be imposed on industry? What data should they share? What processes should be followed for sharing data on suspicious activities and with whom?

Industry should initiate an intra-industry dialogue, across sectors, to establish minimum standards for self-protection, data standards, and reporting procedures.

North Sea governments have made significant efforts to develop dedicated CMIP strategies. Such efforts draw on existing maritime security coordination structures. Policy integration, clarifying competencies, and identifying responsibilities for internal and external actions continues to be a major challenge. National solutions need close integration in regional seas approaches.

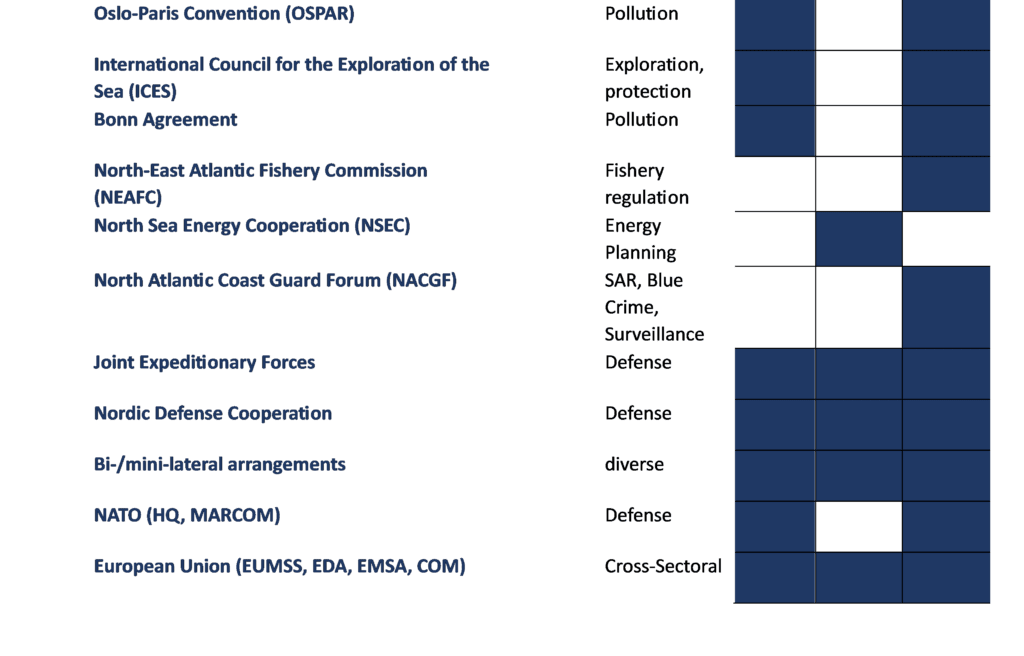

Regional cooperation

A new memorandum of understanding for operational information sharing among North Sea countries is about to be concluded. If and how this arrangement can be integrated into existing institutions is an open question.

8 existing regional institutions provide a framework for cooperation in the North Sea, and in addition to NATO and EU could be used to strengthen regional coordination.

The key policy vehicle in the EU will be the implementation of the Action Plan of the 2023 EU Maritime Security Strategy, while NATO is developing a structure for CMIP at the level of headquarters and operations. Ensuring coherence between these plans, through EU-NATO dialogue, and other instruments, such as the EU’s Common Information Sharing Environment or the European Defense Agency is of essence.

Governance mechanisms in the North Sea

Strengthening protection

The facilitation of information sharing on national developments, industry activity and intra-regional lessons learned continues to be of high strategic importance.

A global process on international norms, legal and technical standards and classifications for CMIP should be initiated, including with countries of the Global South that are vital in the green transition.

An international research alliance on CMIP, initially led by SafeSeas, was inaugurated at the symposium and will be formally launched in spring 2024. Organizations are invited to join the initiative and support the agenda (see Annex).

A follow up meeting on the North Sea is scheduled for May 2024 to be held in Edinburgh, with additional events announced to take place during 2024. A report on CMIP in the North Sea will be developed and published in 2024.

The event was organized, facilitated and supported by the Centre for Security Research, University of Edinburgh, Center for Military Studies & Ocean Infrastructure Research Group, University of Copenhagen, and SafeSeas – the research network for maritime security and ocean governance, with funding by the Center for Military Studies, Edinburgh-Copenhagen Strategic Partnership Initiative and the Velux Foundation.

For further information contact Professor Christian Bueger,